“Blow-out Pockets” in the Colon: Diverticulosis

This is indeed a wonderful world we live in and those of us who are privileged to live at the present time can gain much comfort from the fact that the profession of medicine, with the aid of science, has been able to conquer many of the dreaded diseases of yesteryear. Smallpox, typhoid, diphtheria, and a host of other terrible threats to life, are no longer problems throughout the civilized world. These and many others have definitely been conquered!

Strangely enough, however, new diseases seem to appear almost as quickly as the old ones are mastered.

You will note I have said that they seem to appear. The fact of the matter is, of course, that many of the so-called newly found diseases have simply escaped detection heretofore. With better means of observation and diagnosis the unfamiliar features of certain conditions have now come to light. What was once considered a rare disease is now known to have been a rarely recognized disease.

Somewhere around the time of World War I, the study of the human body by means of the x-ray achieved widespread acceptance by the medical profession. Development of radiography led to the discovery of many curious, hitherto unsuspected defects of the inner man.

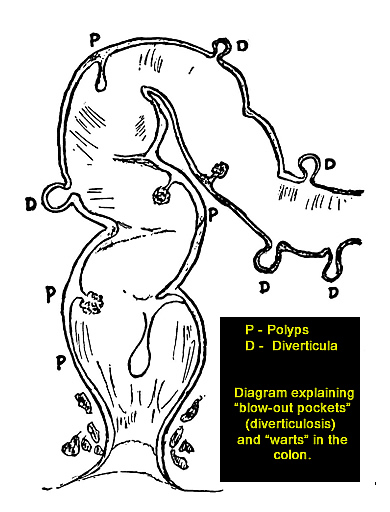

Prominent among these new discoveries was a condition which has come to be known as diverticulosis. Ever see the soft inner tube of a tire? In general, it looks like the colon, although of course, it is of much larger diameter. In looking over one of these inner tubes, you may have seen a place in it that had developed, through weakness, a little pouch. The weakness was not sufficient to permit a blowout, but it did produce a little sac bulging out under pressure of the air in the interior of the inner tube.

Now your colon, too, is a tube. Normally it is not subjected to much pressure, but when you allow constipation to occur and recur and then hurl down into the colon high powered cathartics, pressure does develop. And under this pressure weak spots tend to give way. A small weak spot in the wall of the colon puffs out into a bubble-like sac, or diverticulum. Actual blowouts do not occur very often. Your nerves take care of that.

If the pressure approaches the bursting point rapidly, your nerves send urgent signals to the brain and the resulting pain makes you do something about it. When, however, the pressure is more gradual and continuous, the process of sacculation is not acutely painful. It is for this reason that actual perforation or blowing out of the wall of the colon rarely occurs, and then seldom as a result of pressure. It actually does occur all too frequently in a manner which I shall describe later.

Let’s see, now, what happens after the little pocket in your colon has been established.

Having a “small change” pocket in your colon, you now proceed, like a little boy, to collect things in that pocket. Small things, like seeds, which come through the upper intestinal tract undigested, or small particles of undigested material, hard feces, lodge themselves in the sac or diverticulum. Over a period of time, particles of mucus and feces become adherent. Sometimes undigested fibers of food get entangled in this.

It is then, because of the bacteria that are normally present, that active trouble starts. Putrefaction in this little sac gives products that are irritating to the lining of the sac and also to the lining of the colon when poured out into the large bowel. Through this irritation, the lining of the colon becomes irritated and reflexly, the organ contracts at various places into spasms.

At this point, the injury is compounded. The spasm interferes with the normal flow of material through the digestive tube. In ordinary language we call this symptom constipation.

A stagnation of bowel content, aided and abetted by the spasm, increases the pressure in the colon. More and more weak spots give way. Instead of one, we now have a number of little pouches or sacs which, of course, present increased opportunity for putrefaction and infection.

The condition is now known to doctors as diverticulosis. In itself, this condition is not a dangerous one. However, it is far more serious than is usually realized, since it always presents the possibility of perforation and is almost invariably associated with a greater or lesser degree of colitis. If the sacs themselves are acutely inflamed, they constitute what is known as diverticulitis, a condition that can give many symptoms identical with appendicitis.

Should perforation occur, the problem is immediately a surgical one, since peritonitis is an immediate danger. Many cases diagnosed as appendicitis are found, upon operation, to be in truth ruptured diverticula.

Even before getting that far, diverticulosis is still a matter of the gravest concern and merits deepest attention. If neglected, colitis is the almost certain result and cancer is always a possible result!

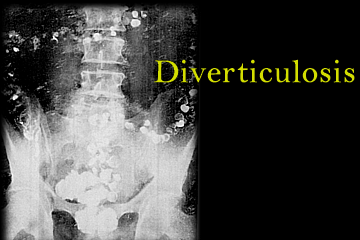

How can this state of affairs be determined? Firstly, by means of a rectosigmoidoscopic examination, the existence of these diverticula can often be proved by viewing them through the instrument. Secondly, even where they are not visible through the rectosigmoidoscope and their presence is suspected, they can be definitely demonstrated by means of what is known as a barium enema study of the colon.

This is a relatively simple and painless procedure. A certain solution is given as an enema and the colon is examined during the passage of the material up the colon. Subsequently, the colon is examined when half the material is expelled; later when all of it is presumably expelled. In such cases, if diverticula are present, they may be very clearly outlined in shadow on the x-ray plate.

What is to be done when the existence of the condition is so determined? The patient must realize that his diet has to be under constant watch, lest he eat something which, on passing through the intestinal tract undigested, might find a resting place in one of these diverticula. Still further, the patient should be put on notice that he is to abstain forever from using cathartics, since anything which would increase pressure in the colon would invite extermination by way of perforation and peritonitis. Under these circumstances, the same thing may be said of so-called high calonic irrigations.

TREATMENT

What should a person with this condition do in order to limit the spread of the condition and prevent complications from occurring?

Treatment requires the very best of medical and surgical judgment. While diverticulosis cannot be eradicated by proper treatment, two things of a constructive nature may definitely be done. The condition can be kept from progressing any further, by removing such causes as constipation, avoiding cathartics, avoiding heavy lifting, etc. The existing diverticula can be spared irritation by avoiding irritating enemas, harsh cathartics, irritating foods, etc. In this manner, the patient can be spared the complication of diverticulitis.

Should diverticulitis occur, it is by no means the serious thing it was in the days before the sulfa drugs and the anti-biotics. With these two very useful implements at hand, most cases can be definitely controlled. Only where the diverticulitis has proceeded to the point of perforation need surgery be invoked. Certainly surgery which would have for its object the removal of all diverticula, would be unjustified. In my opinion, and that of other conservative surgeons, the same may be said of colostomy. It is not justified in any but exceptional cases.

My own opinion, based on a specialized experience, is that the control of the condition lies largely in the proper diet. With the suitable diet, by far the majority of patients can learn to live with the condition and be the better for the handicap. It is the old story of having an incurable disease and then treating it well. The patient helps his general nutrition, as well as avoiding trouble locally, by learning what is the best diet for himself.

The diet which has given my patients the most satisfactory results is, contrary to general opinion, not the concentrated diet but a bulk diet. When people are put on a low residue diet, there is continuous contraction of the muscular fibres of the colon. This increases the pressure in the colon and thus aggravates the existing pockets and may indeed produce new ones. The bulk diet, however, is well tolerated, is far more convenient to follow, and is certainly better for the patient. It is given in detail in the following paragraph.

Eating plenty of cooked fruits and cooked vegetables, especially the leafy and fibrous vegetables gives bulk to the bowel content. So, too, does coarse bread and cereals. Since proper bulk and consistency serve to stimulate the intestinal musculature, they aid the movement and the tone of the fibers of the intestinal wall. Plenty of water along with sufficient roughage as suggested above will prevent the stool from becoming hard and small—two conditions which aggravate diverticula. On the contrary bland bulk and an abundance of water will aid adjustment of the bowel to the presence of these “blow-out” pockets or diverticula and tend to retard their progression.

Naturally a diet for these cases must exclude articles of food containing seeds since these pass through the food digestion canal undigested and by a perverse fate seem destined to get no where else but into these pockets. Once there, they cause much irritation and lead to some of the complications mentioned above.

Of course, many cases of diverticulitis have come to surgery. In fact, at one time an abdominal operation was performed for the eradication of the condition. During this operation, the entire affected part of the colon was removed. The mortality was so high, however, that it may well have caused the coining of the phrase: “Operation successful, but the patient died.” Later surgeons abandoned this idea and merely made an opening in the colon in order to short-circuit the bowel content. For many reasons this method, however, proved unsatisfactory both to patient and to doctor.

Occasionally, as briefly mentioned before, these little pockets become filled with pus and burst. When this occurs, peritonitis is imminent and more than one case has been diagnosed as appendicitis. Needless to say, when this occurs it is definitely a surgical problem. However, with the present availability of penicillin and other anti-bacterial medicines, such a situation need not be fatal.

Whenever bleeding occurs without the presence of hemorrhoids, one must suspect diverticulosis. Very often the blood is only slight in amount and appears mixed with a stool or with mucus. If the doctor cannot find any “pockets” by means of instrumental examination with a rectosigmoidoscope, he will certainly avail himself of what is known as a barium enema study of the colon. This will very clearly outline the condition. Indeed it is hard to tell the difference from certain other conditions such as ulcerative colitis, cancer of the colon, or polyps without making a series of studies with x-ray enema.

COMPLICATIONS

There is a reason, of course, for the wide variation of symptoms in these cases. The mere presence of a little sac in the wall of the colon by itself does not give rise to symptoms. However, should a hard particle, such as a seed, small spicule of bone or a hard fecal mass fall into this pouch, a certain amount of irritation occurs and this leads to inflammation. The use of harsh cathartics, or of enemas, given under excessive pressure, tend to further irritate. Straining at stool or even strenuous exertion may aggravate the condition. In fact, anything that increases pressure in the abdomen tends to make the condition worse. It is then that the diverticulosis becomes inflamed and acquires the degree of itis—in other words, becomes the disease, diverticulitis.

That the condition can become complicated by the addition of inflammation is definitely the case. About one quarter of all those who have diverticulosis sooner or later develop diverticulitis.

DUTIES OF A DIVERTICULOSIS PATIENT

Avoid food that may deposit seeds and other hard particles in the “pockets,” such as figs, raisins, strawberries, tomatoes, etc. Also avoid eating things with hard particles in them, such as cracked wheat or oatmeal, the husks of which sometimes are to be found in the food.

Avoid gas-generating foods such as cabbage, cauliflower, and Brussels sprouts. Avoid carbonated waters, soda pop, vichy, seltzer, etc. In this way you avoid the danger that comes with distention of the intestines.

Avoid constipation which creates pressure in the intestinal canal. For the relief of such constipation as does occur, do not take cathartics or high colonic irrigations. Instead, take a plain, tepid water enema under low pressure. This will accomplish all that the others hope to do.

To be sure of avoiding cancer, have periodic examinations by your physician and by a qualified specialist in rectal and colonic ailments. This must include instrumental examination of the bowel. Written By: J. F. Montague, M.D., Continue Reading: Warts in the Colon: Polyposis

No Comments